The United States Air Force (USAF) has been historically content to adapt airliners for use as air-to-air refuelling tankers . Why is it now pushing for a ‘Survivable Tanker’ for its KC-Z program, and what does it mean?

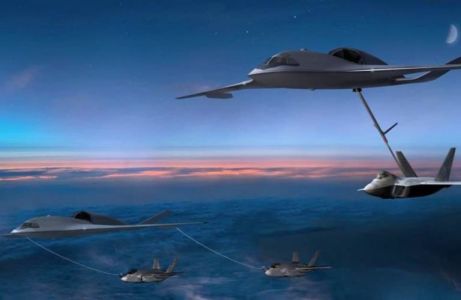

A ‘Survivable Tanker’ design concept for KC-Z. (Lockheed Martin)

The military applications of air-to-air refuelling were first considered during the 1920s and 30s, but it wasn’t until after the Second World War that the newly formed USAF – and specifically, Strategic Air Command – embarked upon the role as we recognise it today. From 1948, Boeing B-29 bombers were converted into aerial refuelling tankers, using the primitive looped-hose method before settling on the flying boom refuelling system that’s still practiced after 70 years. The USAF’s Tactical Air Command also applied the British practice of using the hose-and-drogue – which transferred fuel more slowly, but was less invasive to install – on converted B-50 bombers in the early 1950s, giving rise to a system that has likewise become widely adopted.

The early motivation behind air-to-air refuelling was twofold. Firstly, it allowed aircraft to undetake long range ferry flights to frontline airfields in a much shorter period, speeding the USAF’s ability to respond to crises around the globe. Secondly, aerial refuelling allowed aircraft designers to prioritise aircraft performance over fuel load. The high fuel load of the Convair B-36 Peacemaker allowed it to conduct long range missions unaided, but at the cost of slow speed and a lower operating altitude. Boeing’s B-47 Stratojet bomber on the other hand was optimised for speed and altitude performance, making it more difficult to intercept en route to target. Achieving this performance required in-flight refuellings in order for it to reach enemy territory.

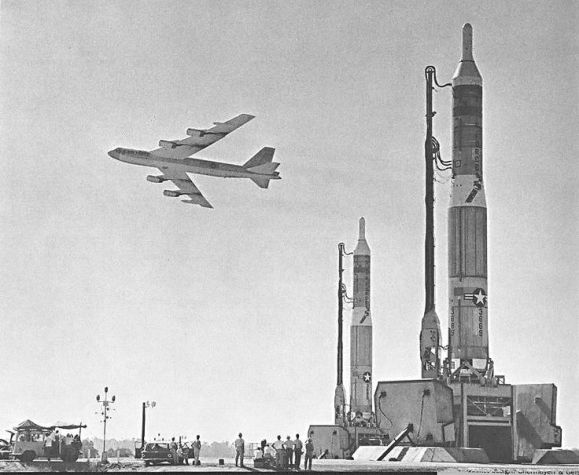

Thirsty work – refuelling the B-47 Stratojet. (USAF)

Oddly enough, some of the design principles of the late 1940s and early 1950s remain current today. The USAF still acquires long-range platforms, but with an understanding that their reach, responsiveness, and loiter time can be further improved by air-to-air refuelling. Much of this has been accomplished with dedicated tanker aircraft built from existing airliner designs. Beginning with the KC-97 (based on the Boeing 377), the USAF went on to acquire the approximately 800 KC-135 Stratotankers (based on the Boeing 367-80 – forebear to the Boeing 707 jet transport) between 1955 and 1965. Today, some 600 KC-135s remain in service, along with approximately 60 KC-10A Extenders (based on the DC-10 airliner) acquired in the 1980s.

Tankers have been critical to the conduct of almost every major air combat campaign conducted by the USAF dating back to the Vietnam War. For such a linchpin capability however, it is odd that there has been no successful foray into a tanker aircraft that is optimised solely for the task of air-t0-air refuelling. Airliners have made popular choices for adaptation into tanker platforms, as they have been a cheap and available option. The airliner’s traditional strengths – long range and large fuel loads – translate well to tanker aircraft, and their cargo and passenger capacity also makes them useful airlifters when deploying and sustaining expeditionary operations.

Grandfather to the modern tanker – a USAF KC-97G (right) refuels a B-47E bomber. (USAF)

Future design requirements for the USAF’s tanker aircraft may be influenced by the shifting nature of how they are employed on operations, emerging and extant threats within a modern battlespace, and the USAF’s future operating requirements.

The KC-X Transition

For the time being, the USAF’s current tanker acquisition program – KC-X – maintains the status quo of applying a converted airliner design into the role of air-to-air refueller. Boeing’s KC-46A Pegasus, a derivative of the 767 airliner, is undergoing test and trials and will begin replacing KC-135s in operational service from mid-2017. The USAF is acquiring 179 KC-46As under KC-X, requiring follow-on acquisition programs to replace the entire legacy tanker fleet of KC-135s and KC-10s.

Coming to airspace near you – the Boeing KC-46A Pegasus refuels an F-16C. (Boeing)

The KC-X transition presents some unique challenges for the USAF. Dating back to its inception in 2002, the program has a long and tortured history, so much so that Allied air forces such as Australia and the United Kingdom were both able to select, introduce and operationally release a modern tanker aircraft over the same period (in this case, the Airbus Defence and Space A330 Multi-Role Tanker Transport). Both countries admittedly acquired significantly smaller fleets than that required by the USAF, however Australia and the United Kingdom are now in a position to appreciate and develop how modern tankers can be operated in a battlespace. For its part, the USAF will soon begin operating a modern tanker, but must balance this against a fleet of legacy aircraft for this generation – and potentially the next generation to come.

In all likelihood, the lengthy process of replacing KC-135s and KC-10s means the USAF will have to retrofit many of the new systems being brought about by the KC-46A, especially if legacy tankers continue serving until the 2040 timeframe. The USAF has conducted trials with Large Aircraft Infrared Countermeasure (LAIRCM) systems on its KC-135, and is also considering whether to apply systems such as Link-16 and Beyond Line-of-Sight Communications.

A LAIRCM system is visible here, just aft of the wing, on the underside of a KC-135 during a 2011 trial (USAF)

Once it arrives in widespread service however, KC-46A will hopefully inform the USAF of the requirements of the tanker programs that will replace the remainder of the legacy tanker fleet – titled KC-Y and KC-Z. It’s up for debate as to whether KC-Y will be a competition for an existing airliner-based tanker, or a sole source acquisition of more KC-46As (or indeed, a modified variant of the Pegasus). The KC-Y acquisition will take place over the course of the mid-2020s, whilst KC-Z – a potentially cleansheet design, one not converted from an existing aircraft – will come into service in the mid-2030s. The USAF can expect its 179th KC-46A to roll off the production line in 2030, by which time its understanding of how tankers are utilised within a battlespace will have grown significantly.

Shifting Role

Modern tanker contemporaries are demonstrating the benefits of aircraft that are ‘smarter’ and more flexible in their employment. One example can be found with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) KC-30A Multi-Role Tanker Transport (MRTT) – a derivative of Airbus’ A330-200 airliner – deployed in the Middle East. Much like its USAF counterparts, the KC-30A flies racetrack patterns within the battlespace, which keep it away from busy airspace and allow receiver aircraft to rendezvous at a pre-arranged space if they require fuel. Using the Link-16 network, the KC-30A crew can also find receivers, determine their fuel state, and bring the fuel to them if so required. The additional situational awareness provided by Link-16 translates to the tanker crew allowing greater persistence in air operations for strike aircraft. By bringing fuel across the battlespace, the tanker can allow strike aircraft to remain in proximity to ground units that they are providing close air support to.

More time over targets – RAAF F/A-18A Hornets over Iraq (RAAF)

More upgrades for tankers are close on the horizon, with some revolutionary potential for how these aircraft operate. In March 2017, the RAAF announced a deal with Airbus Defence & Space to develop a number of upgrades for the KC-30A, the first being Automatic Air-to-Air Refuelling (A3R) – essentially making the process of boom refuelling autonomous. Whilst the RAAF KC-30As will continue to carry a human crew, the process of refuelling could be made quicker and safer (especially considering the risk of refuelling booms damaging the surface coating of stealth aircraft). The success of A3R raises the real prospect that tanker aircraft designed post-2030 will fly ‘optionally manned’ missions, releasing them from the limitation of onboard crew endurance limitations. Such tankers could remain ‘on station’ for significantly greater periods, especially if they themselves can be refuelled in a battlespace by another tanker.

Other upgrades for tanker aircraft will become apparent in the next decade, as manufacturers seek to capitalise on the significant ‘real estate’ possessed by these platforms within a battlespace. Far from being just a gas station in the sky, future tankers could also be used to supplement specialist roles, being used as a communications relay for surface and air combatants, and act as a ‘flying server’ that combines multiple sources of information within a battlespace, and disseminates product across multiple networks and to many receivers. Technology that once necessitated a dedicated platform – whether it be communications, electronic warfare, or intelligence-gathering in nature – might also be incorporated as a ‘plug-and-play’ system for a tanker, carried on board as the mission demands.

Connected to the future – a RAAF KC-30A (right) refuels a USAF F-35A (USAF)

Surviving a Battlespace

For KC-Z, the USAF wants to adapt many advances found in modern tankers with one key distinction – the aircraft also needs to be ‘survivable’. Modern tankers are fitted with a host of self-protection systems that allow them to operate in a low threat environment, including electronic warfare and awareness systems, LAIRCM, and countermeasure dispensers. But their airliner heritage betrays their survivability against medium- and high-end threats from radar systems and combat aircraft. Achieving the desired survivability for KC-Z requires a cleansheet design with performance, reduced radar cross-section, or new self-defence systems that provide adequate protection in a contested battlespace.

Why hasn’t the USAF required Survivable Tankers before? There’s a handful of explanations. Firstly, legacy tankers have traditionally provided fuel at the doorstep of an enemy’s Integrated Air Defence System (IADS), the collective network of ground-based radars, missile and artillery units, and fighter aircraft. The area of influence of a modern IADS is increasing, and stealthy aircraft may get close enough to launch long-range air-to-air missiles against friendly tankers. In such a scenario, an unprotected tanker would have to provide fuel at much further ranges from a battlespace, requiring strike aircraft to rely on their own fuel to accomplish their mission. A Survivable Tanker would not present such a liability.

“Where you are going, I cannot follow”. An artist illustration of the KC-46A refuelling a B-2A Spirit (Boeing).

Beyond this, a Survivable Tanker that could operate in a contested battlespace presents opportunities that simply never existed before. Taking modern operations in Iraq and Syria for example, the RAAF’s KC-30A will accompany F/A-18 Hornet strike aircraft from their base in the Middle East to strike Daesh targets. The KC-30A will top up the Hornet’s tanks during the sortie (as well as other Coalition receivers), providing flexibility and loiter-times to provide responsiveness to dynamic missions, increasing the quality of support they provide to ground commanders. Accompanying strike aircraft allows the tanker to effectively act as an extra set of fuel tanks during the course of a nine-hour mission.

These missions are being conducted in a permissive airspace, however. If the KC-30A were supporting F-35As in a contested environment, for example, the tanker would have to ‘leave’ the strike at the doorstep of an enemy IADS. A Survivable Tanker such as the KC-Z could potentially continue through an IADS threshold, remaining close enough to continue providing fuel and increasing the loiter time of strike aircraft. Whilst strike aircraft have been operated by the USAF for some 30 years, the ability to make them a persistent asset in a battlespace is a powerful tool for air commanders, and the introduction of the F-35A and B-21A will only provide them with more assets to carry the element of surprise.

What Challenges Exist

Designing a Survivable Tanker will likely require KC-Z to possess a small radar cross-section, although not necessarily be ‘stealthy’ to the same extent of an aircraft such as the B-2A Spirit. It may also possess self-defence systems similar to those employed by current tankers, or develop these systems further, with Lockheed Martin suggesting lasers that can shoot down incoming missiles. In discussing KC-Z survivability requirements, the USAF has also spoken about ‘signature management’, suggesting a means of manipulating how the aircraft may be perceived or detected in a threat environment – although details of how this would be achieved are scant.

A cleansheet KC-Z design might deliver other strengths not enjoyed by other tankers. By not adapting an existing airliner, KC-Z can be further optimised for fuel load, efficiency, and low-observable design, and forego cargo and passenger carrying capacity. The airlift capacity of existing tankers is exceedingly useful when deploying forces abroad (especially for smaller Air Forces that may lack the strategic airlift depth of the USAF). But during dedicated tanking missions, that capacity is un-utilised space, incurring a performance penalty as the aircraft commits to its primary role.

Boeing and Lockheed Martin have already begun pitching their proposals for KC-Z, and it’s a safe assumption that Northrop Grumman will consider bidding, given its experience with low-observable designs. Design solutions may include flying wings, stealthy transports, and the use of Blended-Wing Bodies. Ironically enough, the design of KC-Z may go on to influence the design of future generations of airlifters and airliners, rather than the other way around.

The Boeing X-48, a remotely-operated flying model intended to test blended-wing body designs (Boeing)

Building a Survivable Tanker presents the risk of promising the USAF their cake and eating it too, however. Low-observable design is by no means a simple science, but air-to-air refuelling practices – especially established methods such as a flying boom, or hose-and-drogue pods – present unique challenges, even before they’re mated with a new aircraft. Existing modern tankers capitalise on the known aerodynamic performance of airliners, and even then present complications. For example, efforts to adapt existing refuelling systems into the Boeing 767 and Airbus A330 have been frustrated, leading to delays and re-designs.

Applying these refuelling systems into a cleansheet design- even one purpose-built as a tanker – could prove still problematic, especially if the KC-Z’s survivability is contingent on the aircraft having a reduced radar cross-section. Refuelling booms and hose-and-drogue refuelling pods require a delicate aerodynamic balance in order to be effectively used. In all likelihood, KC-Z will have a reduced radar cross section from frontal aspects, but compromise its ‘rear quarter’ so that it can be optimised for its tanking systems. Whilst hose-and-drogue refuelling pods can be internalised, the refuelling boom – which measures up to 17 metres – has to be mounted securely to be of any value.

When deployed, these refuelling systems must prioritise their aerodynamic performance – it’s unlikely these systems can be built to be ‘stealthy’. That design liability becomes important when the USAF considers how such a platform can be operated within a battlespace.

Uniquely shaped, but not ‘stealthy’ – the KC-46A boom (USAF)

Applying air-to-air refuelling within a contested battlespace is likely to be a challenge unto itself. Much of the USAF’s operational experience with fielding tankers has been built around the aircraft flying in environments where their safety from surface or air threats is largely assured (or the risk that they will be shot down is simply accepted). Introducing KC-Z into a contested battlespace is new ground that will likely require the USAF to model its application through the extensive use of simulations. It may even have to take an existing aircraft with a similar radar cross section, and use it as a ‘proxy’ for mission rehearsals and testing. During a refuelling period, receiver aircraft are often not performing their primary role, which has implications for air and surface assets within the battlespace.

The Shape Of Things To Come

If the USAF follows through on KC-Z, the potential impact on air-to-air refuelling is staggering. The USAF will be uniquely placed to deliver sustained air power effects within a contested airspace. Allied air forces will likely rely on the USAF KC-Z fleet to likewise operate within a contested battlespace, lest they field their own Survivable Tanker. The tanker market will see a fork in the road between Survivable Tankers, and those similar to current tanker aircraft – able to perform a strategic airlift role, as well as air-to-air refuelling in permissive environments.

There can be no understating the importance of air-to-air refuelling for the future of the USAF – and the evidence is in the organisation’s past. The global reach and persistence throughout the USAF’s history has been accomplished through tanking. For that status quo to continue, new aircraft – whether they be adapted airliners under KC-X and KC-Y, or a cleansheet KC-Z design – must be a priority. The alternative is that the USAF continue operating an ageing tanker fleet that can’t maintain pace with modern tanker operations. This will limit the USAF’s range and duration on operations, taking it into a downward spiral that will also affect Allied partners.

How KC-Z opens up this future exactly is, right now, anyone’s guess. The USAF’s Air Mobility Command is not slated to release further information about its future tanker requirements until mid-2017.

Beevor still manages to show his talent is for weaving detail amongst the bigger picture, and it makes for some heavy reading. There’s entertaining quips (my favourite: a British soldier in North Africa, asked how many POWs he’s taken, and replying “Oh, I’d say a few acres worth”). But in a conflict where so many lost their lives, there’s some harrowing chapters, especially when names are given. The conflict witnessed a wholesale loss of human life that will cause you some despair for the human race.

Beevor still manages to show his talent is for weaving detail amongst the bigger picture, and it makes for some heavy reading. There’s entertaining quips (my favourite: a British soldier in North Africa, asked how many POWs he’s taken, and replying “Oh, I’d say a few acres worth”). But in a conflict where so many lost their lives, there’s some harrowing chapters, especially when names are given. The conflict witnessed a wholesale loss of human life that will cause you some despair for the human race.